The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker

and

Epic Mickey

A critical comparison demonstrating the usefulness

of Janet Murray’s pleasures of digital interactive media.

Bradley C. Buchanan

ETC Fundamentals: Video Game Report

November 4, 2011

As video games develop into a dominant media form, it is helpful to have tools with which to analyze and compare them to one another. One of the traditional tools for analyzing media is Aristotle’s Poetics, which describes the elements of drama. While this tool is helpful for analyzing interactive media, it is not complete. A more recent measure that can supplement Poetics is Murray’s interactive pleasures. To demonstrate the usefulness of this newer tool, here is a critical comparison of The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker and Epic Mickey. Aristotle’s standards suggest that Epic Mickey is a superior artistic work, but Murray’s work explains why Wind Waker is a better game.

The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker is a third-person action-adventure game released for the Nintendo GameCube in December 2002. It was developed by Nintendo EAD and directed by Eiji Aonuma.

Epic Mickey is also a third-person action-adventure game released for the Nintendo Wii in November 2010. It was developed by Junction Point Studios and designed by Warren Spector.

At first glance, these two releases have much in common. Both are 3D action-adventure games with platforming, combat, and puzzle-solving elements. They each last about twenty hours[i]. Each game embraces a cartoony art style. Both games tell a story about uncovering past events, and reconciling them in the present. One might argue that Epic Mickey owes everything to the Zelda franchise; it even includes a direct reference to the first Zelda game[ii].

Yet these two games present different experiences, and they succeed in different ways. A deeper examination will reveal those differences and explain why Wind Waker, in spite of being an older game and inferior according to Poetics, is more successful than Epic Mickey.

Aristotle’s Poetics

In his work Poetics Aristotle presents six elements of drama, which he ranks from most important to least important. One modern translation of these elements lists them thus: Plot, character, theme, diction, music, and spectacle. Plot is judged most important, and spectacle the least. Epic Mickey fares well by Aristotle’s standards. Wind Waker does not, nearly reversing the elements in order of importance.

Plot

The plot of a work describes the sequence of events that take place, and the cause-and-effect relationships between those events that create meaning for the audience. Both Wind Waker and Epic Mickey feature prominent, complex plots.

In Wind Waker, a young man (Link) is thrust into adventure when his sister (Aryll) is kidnapped by a giant bird. He acquires passage across the Great Ocean on a pirate ship and attempts a rescue, but fails because a powerful wizard (Ganon) stands in his way. Link meets a talking boat who helps him retrieve a magical sword to defeat Ganon. In their second confrontation, several revelations occur – the talking boat is an ancient king of a kingdom frozen in time, the pirate leader is a reincarnated princess of that same kingdom (Zelda), and Link and Ganon are destined enemies. Aryll is rescued, but the quest to defeat Ganon continues with a search for a mystical artifact and awakening two sages to restore the sword’s power. In the end, Link and Zelda defeat Ganon, and the king wishes that his old, flawed kingdom would be destroyed, so that Link and Zelda can have a hopeful future on the Great Ocean.

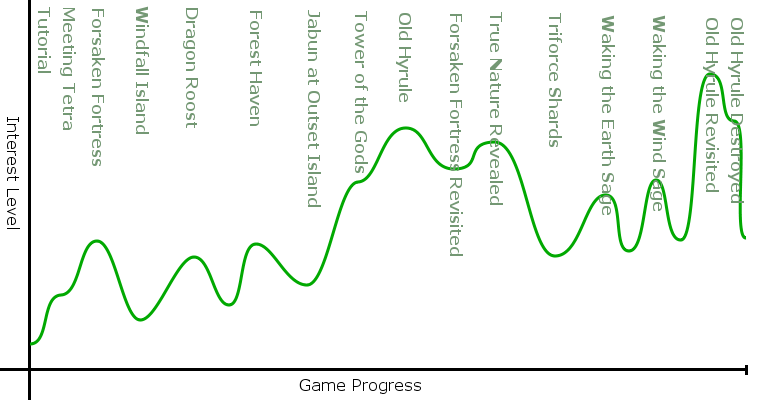

Figure 1: Wind Waker‘s interest curve

Wind Waker has an imperfect interest curve, with a large jump in intensity near the center of the game when Old Hyrule is introduced, followed by a decline back to an ordinary interest level until the end of the game. The last third of the game has many goals that can be completed in any order – the sequence shown in Figure 1 is one possible experience. This leads to an unpredictable interest curve and one of the weakest elements of this game. Making this section shorter might have resulted in a stronger interest curve overall, but at the cost of some player agency.

The story of Epic Mickey: Before he was famous, Mickey Mouse accidentally created a monster (the Blot) that terrorized a world designed for forgotten Disney characters. Years later, he is kidnapped by the Blot and trapped in this world (Wasteland) where he must come to terms with the damage he’s caused, reconcile with the residents if he can, and find a way to escape. Mickey travels around Wasteland searching for rocket parts to help him escape. When his task is almost complete, there is a confrontation between him and his brother Oswald where it is revealed that Oswald’s girlfriend was martyred to seal the Blot away many years ago. After this confrontation the blot is released again, and Mickey and Oswald must work together to defeat the Blot once and for all. In the end, Mickey returns home.

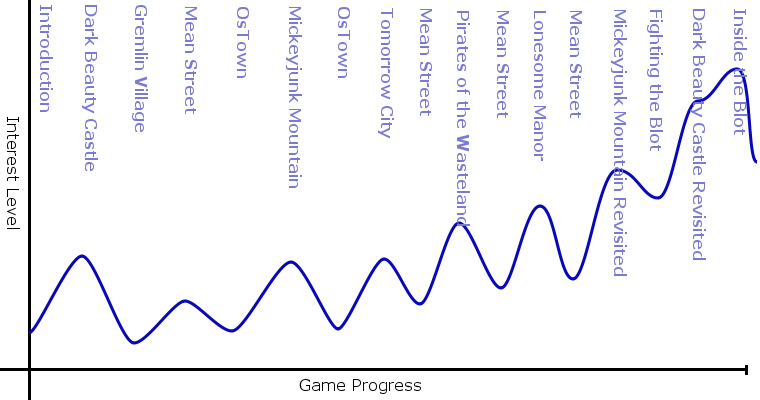

Figure 2: Epic Mickey‘s interest curve

Epic Mickey’s interest curve is closer to ideal than Wind Waker’s. It begins with a strong hook, followed by a climbing oscillation to a dramatic conclusion. Because of this, the game does a good job of creating anticipation for the next scene at all times.

Both games tell two stories; one story consists of events that happened a long time ago, and the other of events the player enacts. Wind Waker tells the story of the fall of Hyrule in the past, and also the present story of Link’s quest to rescue Aryll, and how in the process he saves the Great Sea from evil. Epic Mickey tells the story of the original Blot disaster and the price Oswald and Ortensia paid to save Wasteland, and also the story of Mickey being trapped in Wasteland, and how in his efforts to escape he learns to take responsibility for his actions and defeats the Blot. Both games have a strong ending because they wrap up two stories in one denouement.

Epic Mickey’s plot is richer than Wind Waker’s in several ways. Epic Mickey does a better job of presenting multiple perspectives on its core conflict. The player hears commentary on the situation from Mickey, Oswald, and a number of other prominent residents of Wasteland, and they express different valid opinions throughout. Wind Waker’s central conflict is more black-and-white, with little room for sympathy with the evil Ganon.

Character

Both Wind Waker and Epic Mickey present strong primary and secondary characters. Main characters in both games have multiple defining characteristics and complex motivations.

In Wind Waker the protagonist is Link. This character is mostly a blank slate for the player, but he does have some core characteristics. Courage is Link’s primary attribute. The gameplay is designed to make Link a generous and helpful character. He is intelligent and emotionally open – deception is rarely an option for the player. Like Link, Mickey is a courageous character. He demonstrates a generosity to the point of sacrifice when he gives up his heart to save his friends. However, Mickey is more complex than Link, concealing his role in the devastation of Wasteland for most of the game, and more readily showing emotions like anxiety or skepticism.

The antagonist of Wind Waker is Ganon. He is defined by a thirst for power, and is also cunning, hiding his advantage until the right moment. Epic Mickey’s antagonist is not as subtle; the Blot mirrors Ganon’s thirst for power but not his intelligence, behaving somewhat like a natural disaster.

Both games feature secondary characters in peril. Wind Waker features kidnappings prominently as first Tetra and then Aryll are kidnapped by the giant bird. Epic Mickey follows suit at the end of its plot, when the Blot takes Gus and Oswald. However, Epic Mickey also features a distressed character in its past plot: Ortensia, Oswald’s girlfriend. In both games, these secondary characters keep the stakes high and encourage the player to continue.

Theme

It’s best for a work to have a meaningful theme, and for all elements of that work to support the theme. Video games often have trouble with this.

Wind Waker has a number of themes. The strongest of these are probably courage and freedom. Although these are not the most powerful themes, they are well supported within the game. The setting (the open ocean) and key plot points and objectives (freeing imprisoned characters) reinforce the freedom theme nicely, while the many challenges that Link faces remind the player that this is a game about courage.

Epic Mickey’s central theme can be described as “living with the past and accepting responsibility for one’s actions.” There are subplots of self-sacrifice and forgiveness, but responsibility is the theme most directly reinforced by the game’s mechanics. These are more specific and powerful themes than Wind Waker wields.

Diction

Both Wind Waker and Epic Mickey use written text, with the one exception that Epic Mickey’s prologue and epilogue are narrated with voiceover. Within this context, both games do a good job of giving different voices to different characters.

In keeping with Zelda tradition, the protagonist of Wind Waker is mute. Other characters are all given distinct speech styles. Their tone varies with the character’s personality, status, and the message they are trying to convey. Characters joke, speak ironically, and express intense emotion. There is not much in the way of verse, though the game’s opening is notable for relating its backstory in the style of a medieval fable, with stained-glass illustration and music in a late-Renaissance style.

Epic Mickey also has a wide variety of voices, and benefits from having a rich Disney history to pull from and established characters with established voices that it can use. The tone shifts between serious and comical. However, the game does not exhibit irony, sarcasm, or metaphor to the same degree that Wind Waker does. The game is also guilty of assigning the same voice to a group of characters – all of the gremlins, and most of the residents of OsTown, speak the same way.

Music

One of my favorite characteristics of the Zelda franchise is that it has wonderful music, which is often a story element and is imbued with magical power within the world. Wind Waker is no exception. In particular, the score of Wind Waker is captivating because it successfully evokes the Great Ocean setting. One thing that Wind Waker does magnificently with its music is that combat music is partially composed by the player. Attacks are accompanied by orchestra hits in specific chords and rhythms, and certain attack combinations produce musical resolution. This is a truly great accomplishment of dynamic music. Finally, in the visit to Old Hyrule in the center of the game, it’s the fragmented music that tells the player that they are in a timeless space.

Epic Mickey’s music is somewhat less memorable, on the whole. It has a more whimsical tone than Wind Waker does. It avoids synthesized music in favor of an orchestral score. In doing so it feels much like a Disney game, but less like a video game. Almost all of the music in the game does reinforce a sense of uneasiness. It’s possible that this discomfort is meant to specifically support the game’s theme of taking responsibility, like a nagging guilt that the player cannot escape.

Spectacle

Wind Waker is visually striking. The aesthetic design is a topic of debate among fans of the series, as many wanted a grittier, realistic style. However, the more cartoony choice is a good match to the narrative. Zelda is always an iconic hero’s journey with exaggerated characters, and the cartoony style lends itself to this. The game also has the most unified aesthetic of any Zelda to date. It’s worth noting that the cartoony style did not prevent the game from feeling “dark.” A sense of genuine peril is maintained, and the colors palette and visual effects allow the developers to create frightening and alien environments.

In terms of spectacle, Epic Mickey disappoints. The game’s final visuals don’t live up to the strange, dark, and whimsical concept art. Although its world is richly detailed and the game is running on newer hardware, it doesn’t look half as good as Wind Waker. One reason for this is the camera/environment relationship. The camera does a poor job of directing the eye to points of interest in Epic Mickey. The environments, though full of interesting landmarks, are rarely designed with cinematic framing in mind. There are almost no vista moments, where one rounds a corner and sees a spectacular new landscape. Instead, environments feel arbitrary, inorganic, and often claustrophobic. This is an ironic failure for a game set in an upside-down Disneyland. The theme park is designed to create these vista moments, but Epic Mickey seems to avoid them. This is a shame; frequent vistas of a devastated Wasteland would powerfully reinforce the theme of Mickey’s culpability.

Murray’s Interactive Pleasures

In Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, Janet Murray describes three pleasures that are dominant in digital interactive media: Immersion, agency, and transformation. These pleasures are similar to Aristotle’s elements of drama, but they reveal something new about interactive experiences. According to Aristotle’s criteria, Epic Mickey is a superior work because it has a stronger plot, characters, and theme. Murray’s interactive pleasures will turn the tables, and demonstrate that Wind Waker uses the strengths of its medium more effectively than Epic Mickey.

Immersion

Murray describes the power of virtual worlds that are real in effect, if not in fact, as immersion. She explains that one of the strongest factors in creating immersion is a consistency of imagination. Wind Waker demonstrates a much higher immersion factor than Epic Mickey.

The immersion factor in Wind Waker is sky-high. A major reason for this is the sheer quantity of interactive elements in the world. Though it may seem odd to fill the virtual world with pointless objects like breakable pots, throwable rocks, and cuttable grass, it’s these small details that make the Great Ocean seem like a real place. Everywhere the player goes, the world is ready to respond to their presence. Signposts can be chopped up into pieces. Trees can be bumped, causing leaves to fall. Neutral characters will glance at Link if he walks near, and cower if he brandishes his sword. There’s no dramatic reason for these interactions, but it keeps the internal logic of the world consistent with the player’s expectations.

The world design creates a playground for the player’s imagination. Players are encouraged to challenge themselves to reach high rooftops and distant landmarks. The ocean theme of the world means there are very few arbitrary walls – one can jump out of the boat and swim at any time. In addition, the menu screens are all appropriately themed to the world as if the character is examining his inventory, not the player. These elements produce such a strong consistency of imagination that it’s hard to not actively create belief while playing Wind Waker.

Epic Mickey fails to create the same sense of immersion. Like Wind Waker it contains breakable containers that serve no dramatic purpose, but they are few and far between. Worse, these containers often take different shapes that suggest different interactions, but the only allowed interaction is to smash them with a “spin move.” Already there is a lack of interactive imagination.

Epic Mickey’s strongest attempt to create this immersion lies in its paint/thinner system. In the game, Mickey carries a magic paintbrush that can be used to erase or restore characters, objects, and parts of the landscape. This system, used for combat and puzzle-solving, can also be applied in hundreds of nonessential places throughout the game; indeed, nearly every scene can be repainted bright and colorful, or thinned dull and dreary. Though this system is as ubiquitous as Wind Waker’s mundane objects, it falls flat for three reasons. First, it always feels planned. Erased objects are always visible in a semitransparent form. This makes it obvious that the developers planned for the player’s specific action, and removes the feeling of freedom. Second, the paint/thinner cuts the player’s interaction options to one, and breaks the consistency of imagination. While the mundane mechanics of Wind Waker enrich the experience because they are consistent with the player’s expectations, painting in Epic Mickey might color an object, or create a whole new object, or trigger some arbitrary world event. Finally, the painting/thinning interaction is not as viscerally satisfying as it should be. A chunk of the game world appears or disappears, with a barely noticeable sound effect. Compare that to the satisfying, audible slice of cutting grass in Wind Waker. Painting as an independent action is not as satisfying as it should be.

Agency

Wind Waker’s immersion and its agency are closely tied, because its consistency of imagination is demonstrated through predictable reactions to player input. On a small scale, every single interaction produces a sense of agency because there is always a logical reaction. Even something as absurd as striking one’s sword repeatedly against a wall produces the correct response: A jarring

clang,” a recoil animation, the physical effect of being pushed back from the wall and a stun as the player’s control is suspended for a moment. The effect is even greater with sensible actions. The game develops the player’s confidence that each intentional action will be met with a reasonable reaction. Many of the game’s core puzzles depend on this principle, presenting the player with a brand-new situation and depending on their trust that the world will respond to them.

Wind Waker is highly dependent on spatial navigation as a pleasure. Major events in the game are built around “dungeons.” Here, a dungeon is a nonlinear spatial puzzle gated with keys, combat, and logical challenges. While in a dungeon the player is forming a mental map of the physical space and a corresponding map of the puzzle space, seeking the sequence of interactions necessary to solve the puzzle. This dungeon pattern is repeated throughout the Zelda series, and fans describe dungeon navigation as a primary pleasure of the Zelda experience.

The game succeeds on a story level, but in a limited way. The player has no control over the story; they can change the sequence of events, but will always reach the same conclusion. However, the game is careful not to take action on behalf of the player; the story simply does not advance until the player plays along. This is also Link can be named by the player, and why he has no dialogue. This nonintrusive attitude toward the protagonist’s actions creates a feeling of narrative agency where there is little. Although the plot is predetermined, the player can always say, “I got myself into this.”

Epic Mickey’s takes the opposite stance on player agency. As discussed regarding immersion, the small interactions of the virtual world fail to create the logical reactions that build up a strong sense of agency. There is some attempt at this, but it is not up to Wind Waker’s standards.

In Epic Mickey, the pleasure of spatial navigation is nearly abandoned. The dungeon concept of Zelda is replaced by something more akin to a gauntlet: A one-way linear sequence of encapsulated puzzles and combat scenarios. Consequently the player does very little mental mapping, and is denied the pleasure of navigation. The one-way structure supports the game’s theme of living with one’s mistakes, but it is easy to imagine how this theme could have been upheld by a more open environment.

On the other hand, Epic Mickey tackles narrative agency on a level that Wind Waker never does. Although the largest story arc is fixed, the player is given control over various subplots. They can ignore these subplots, or resolve them in different ways. The game’s cinematic ending is then customized to create a cumulative acknowledgement of the player’s decisions. These subplots can also hide entire quest chains mid-game, so the player has considerable control over their own experience. Thus, Epic Mickey has less mechanical agency than Wind Waker, but more narrative agency.

Unfortunately, Epic Mickey also makes the mistake of acting on behalf of the player. On some level this is acceptable because Mickey is an established character, but sometimes key decisions are made without player input. The most glaring example takes place at the climax of the story, where Mickey willingly gives up his heart to save Gus and Oswald. Here, even the non-choice between “yes” and “uh-huh” would have been preferable if only to make the player physically responsible for the response[iii].

Transformation

Wind Waker is an adolescent power fantasy. Much of the player’s time is spent in combat or avoiding dangerous traps. The other major activity in the game is sailing, an extrinsic fantasy that lends some charm to the experience. This is transformation as masquerade; the enchantment of being somebody else. Wind Waker does this well, even if the mask is just another archetypal hero.

Transformation as variety does not show up as much in Wind Waker. Because of the simplistic nature of its conflict, there is not much variation on its themes. The game can be replayed, but it does not change significantly. The only space that is exhaustively explored is the player’s navigational freedom. Indeed, progress in the game is directly tied to the player’s power to navigate the world.

As for personal transformation, Wind Waker is not likely to enable a life-changing experience for anyone. Its themes are not powerful or direct enough for that. The quality of its immersion might help one overcome a fear of spiders, or encourage one to try sailing, but there is more powerful escapism in it than life-changing meaning.

Epic Mickey also plays to the transformation as masquerade, to the fantasy of being Mickey Mouse. The development team went to great pains to capture Mickey’s animation, in order to help the player feel like they really are the famous character[iv].

In variety, Epic Mickey works hard as well. It is specifically designed so that a player cannot complete everything their first time through the game. The designers want players to go back and try different choices, exploring the consequences of other options.

This identification with Mickey and the focus on consequences gives the game great potential for personal transformation. It is unfortunate that the game’s low immersion and agency detracts from this potential. Learning that one’s actions have consequences for others is a crucial part of growing up, and if this game has successfully taught that to one player, it has succeeded.

Conclusion

In the end, Wind Waker is the stronger game. Epic Mickey should be applauded as a brave experiment in narrative agency dramatic quality, but it fails as interactive media. It is possible to envision Epic Mickey with a high degree of immersion or agency by taking a few pages from Wind Waker’s book, but as the game shows, one can’t change the past. Murray’s pleasures of interactive media can help to isolate those elements that work from those that don’t. It is up to another game to combine the strengths of these two works and move the medium forward once again, further into dramatic and interactive maturity.

[i] IGN’s review claims that Wind Waker has “20+ hours of gameplay and as much as twice that for completionists.” Ign.com, March 21, 2003. http://cube.ign.com/articles/390/390314p1.html. Warren Spector, director of Epic Mickey, claims it will take “three 20-hour playthroughs to see everything.” Wired.com, November 5, 2010. http://www.wired.com/gamelife/2010/11/epic-mickey/.

[ii] One of the pirates on Tortooga says “It’s dangerous to go alone! Take this,” before handing Mickey an item, a direct reference to the acquisition of the first sword in The Legend of Zelda. http://www.zeldauniverse.net/zelda-news/zelda-reference-found-in-epic-mickey/.

[iii] See every dialogue option in Super Mario Galaxy 2 for an example of this.

[iv] From Epic Mickey’s behind-the-scenes content: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wvDCoQL9b2w.