I gave Dwarf Fortress a good go. Three solid attempts. It’s worth a try, but I’m afraid I’m done with it. Here’s the story:

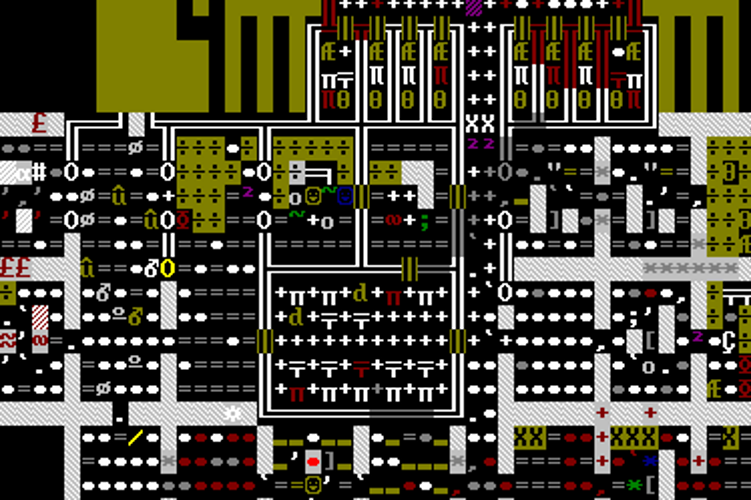

Dwarf Fortress is a simulation game where you direct a group of dwarves to build a fortress and deal with the chaos life throws at them. It’s known for having one of the steepest learning curves in computer gaming, played with a VI-esque keyboard command interface, menus many layers deep, and graphics made entirely of text characters. What you see in the screenshot above is part of my last fortress, centered on the kitchen and (manned) still, which are directly north of a long dining hall (see the tables and chairs?). To the west is food storage, and on the very edge you can see the fishery and butcher shop. To the west are two carpenter’s workshops and a mason’s workshop. Bedrooms and offices are in the north. If you’re having a hard time seeing that, don’t worry – I did too, for the first 1.5 fortresses.

Three tries

Because this is a hard game to learn, I first went to The Complete and Utter Newby Tutorial for Dwarf Fortress for help. At their recommendation I also got a tileset to replace the default-text graphics with something nicer/easier. It turns out this didn’t make things easier. The tutorial was also just enough out-of-date to be confusing in several places. I put the game down for a while.

On attempt two I checked the wiki for newer tutorials, and followed them less precisely, with more success. Each tutorial seems to include some critical information that others forget, and you would never realize just playing the game. My second fortress was somewhat successful. Mostly it got tons of immigrants and I ended up with lots of dwarves standing around idle, because I couldn’t figure out how to give them all useful jobs. Seeing disaster looming and wanting to try things differently, I started over.

On attempt three I set out on my own, only using the past tutorials for reference when I forgot an important sequence of commands. Things were going nicely – my population was holding at about 16, and every dwarf had good productive work to do all the time. I had plenty of resources, good management, crafts getting queued up, even my first successful trading agreement. Then dwarves started dropping dead… of thirst. I had the still running night and day, and reserves of wine (dwarves live on alcohol and only drink water in the most dire circumstances, apparently) and these dwarves were just dropping dead from dehydration, when there was drink available around the corner. Oh well. With half of my population gone, I called it and decided I had enough of Dwarf Fortress to consider from a design perspective.

Is it good?

Understand, I’m not upset that things fell apart. Perhaps the central idea behind Dwarf Fortress is “Losing is fun!” and the game does reflect this. Everyone loses, because there is no win condition, but every loss is new and different; it’s the antithesis of boredom.

In one way, the game plays magnificently to the strength of its medium. This kind of calculation and simulation, tracking a million variables and simulating the agency of dozens of denizens is something that simply can’t happen in any other medium. It’s a perfect recipe for emergent behavior and unique experiences, producing stories suggested and shaped by the system but coauthored with the player. Perhaps it is the apex of PC gaming.

Is it bad?

Dwarf Fortress also contains a deep fundamental flaw, that prevents it from being the amazing wonder-game I want it so badly to be: It’s not designed around the I/O.

I’m reading The Art of Computer Game Design by Chris Crawford right now. In it, he explains that I/O is the primary weakness of the computer games medium, especially input. Computers can handle huge amounts of data, but have trouble moving that data between the computer and the player. In particular, it’s extremely difficult to create an input structure that is both expressive and intuitive, and Crawford writes “I maintain that a good game designer should eschew the use of the keyboard for input and restrict herself to a single simple device, such as a joystick, paddle, or mouse. The value of these devices does not arise from any direct superiority over the keyboard, but rather in the discipline they impose on the designer.” Dwarf Fortress’ input is busy, at best, built on a paradigm that isn’t familiar to most people. Expressing yourself to the game is kind of a labor-intensive process.

The cumbersome input might be forgivable if the output wasn’t just as opaque. I don’t mean the literal display using text; while that takes some learning, it’s surprisingly lively and imagination-enabling. What’s missing is powerful, tangible feedback on what’s happening in the game, and on the effectiveness of the player actions. As a result, the player is often unsure of whether they are being successful, or doesn’t see problems coming because the game doesn’t bring them to the player’s attention.

In The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, Jesse Schell describes “the loop of interaction,” whereby the player sends their intentions to the game, and the game must respond with clear feedback indicating whether the player’s intentions were carried out, and probably influencing what the player will do next. Dwarf Fortress is already at a handicap in this respect; the player gives orders but never directly controls the dwarves, so the player’s “actions” are rarely carried out right away. Furthermore, the game fails to communicate critical elements of its rich simulation back to the player which makes it hard for the player to make informed choices. For example, I had no idea my dwarves were thirsty until they were literally dying of dehydration. After three games, I’m not sure how I would have discovered this at all – although there is a page to view a dwarf’s recent thoughts, I never saw anything related to personal needs there.

In summary, I feel like Dwarf Fortress was built first around its simulation, not around it’s I/O design, and – just like Crawford and Schell suggest – it suffers badly for it (as a game… as a simulation, it’s probably just what the designers intended).

Takeaway

I really do love the idea of Dwarf Fortress. Here are the parts I like, and where I think they are done better.

DF is a Large Simulated System. I love games that model the essence of a complex system, like SimCity, Rollercoaster Tycoon. These games often show emergent behavior. Their replayability is through the roof. They really take advantage of the medium, and they are some of the best learning tools in games because freedom to play with a system brings understanding of that system. Good feedback is essential for sims, from SimCity’s R/C/I meters and city advisors, to Rollercoaster Tycoon’s constant stream of feedback about guests’ thoughts and feelings, all sortable and searchable.

DF implements Nurturing as Gameplay. Taking care of virtual characters can be deeply satisfying – Tamagotchi anyone? – and it’s a form of compelling, non-violent gameplay. To be nurturing, though, you must know the needs of your subject. Again, this is an issue of feedback. Rollercoaster Tycoon makes it easy to understand the needs of thousands of guests, collectively or individually. The Sims actually displays meters for how hungry, thirsty, or bored your sims are. Better, each game gives fantastic visual feedback about the characters you are nurturing. Sims dance with joy, throw tantrums, or break the fourth wall and yell at the player when they’re unhappy. Guests in RCT are perfectly expressive for only being a few pixels tall – a single glance will tell you whether a guest is happy, bored, angry, nauseous or tired. I never understood what my dwarves wanted as intuitively as I did the people in these games.

DF creates a Procedural History. For every player the game doesn’t just generate a random landscape, but an entire random history of the world to go with it. I think this is an amazing idea and I can’t think of any other games that do it, but I also feel like it’s underutilized in DF. While it does lend a surprising sense of realism to the world, I never got far enough to really discover that history or connect it to my game. I can’t wait to see (or make) a game that can generate this kind of procedural history, but also carefully weave it into the player’s narrative in a convincing way.